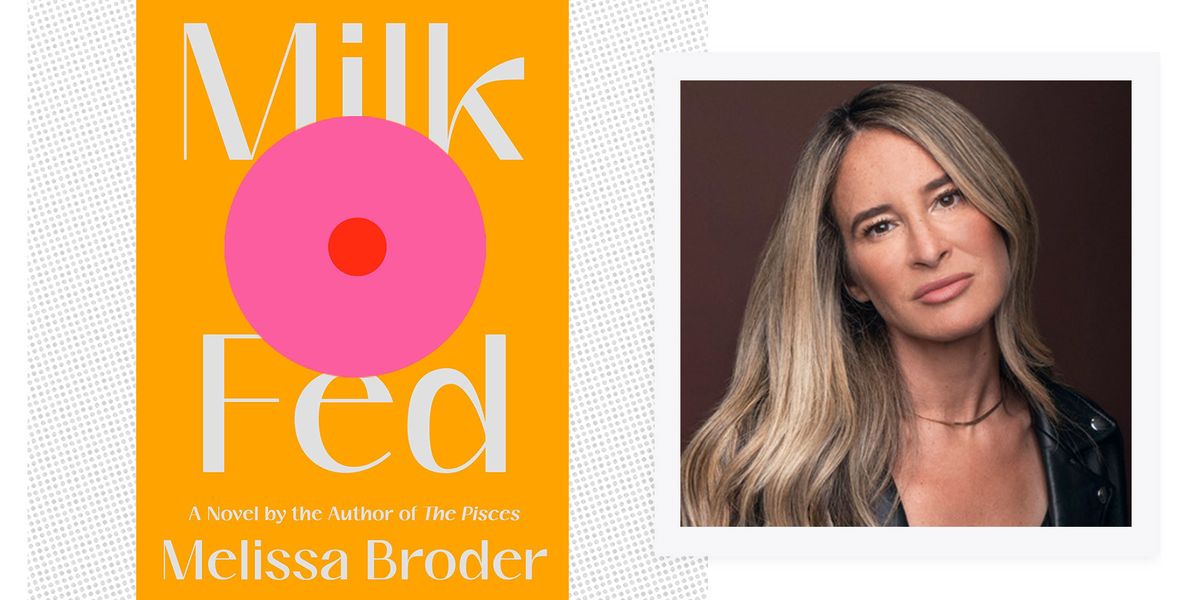

Melissa Broder’s new novel, Milk Fed, grapples with dissatisfaction. It’s a theme that runs through her catalogue more widely, be it her droll-slash-existentially-queasy Twitter handle, So Sad Today, or her celebrated novel The Pisces. This ache for more of everything—more flavor! more passion! more approval! more comfort!—is ultimately impossible to quench, and Broder examines how to live with that infuriating disappointment.

Her latest protagonist, Rachel, lurches between visceral impulses and toxic narratives. She’s been shamed her whole life by her mother and developed disordered eating habits that make her “high on sacrifice.” Nothing adequately compensates: Her job at a Hollywood talent agency feels meaningless and she considers her therapist dubiously qualified at best (“How good could she be if she was willing to deal with Blue Shield?”). When Rachel does open-mic nights, her “alt JAP” persona, clad in Saks Off Fifth, is an obvious outlier amongst the “Moon Juice, organic lip tint, and cocaine” set. Everything in Rachel’s life feels disposable and insufficient until she encounters Miriam, a “kosher coquette” who serves frozen yogurt. Miriam’s presence “giv[es] life to my dead parts,” as Rachel put it, and this hit of intimacy spurs her to make other changes.

ELLE.com spoke with Broder by phone from her house in the Canyon, where she takes breaks from editing her next novel to obsess about her dog Pickle’s engagement with local rodent life. We discussed the influence of Philip Roth, dictating on the 405 in lieu of writing at a desk, and absolving one’s parents (kind of).

Rachel breaks communication with her mother as an experiment, to cut out her destructive refrains. But the book also speculates: when should someone stop blaming their parents? I’d say Rachel still can—24 is pretty young.

Definitely. I think Rachel has some more years left. There’s this idea “who could I have been if I had been raised differently? Kind of like that Pinterest meme: What would you be if you weren’t afraid? [Laughs] There’s that other self.

Seeing your parents as human can be a very gradual process. One of the qualities I value in myself is knowing that I know nothing—like, the Socrates deal. When you start to gain that awareness, you realize your parents know nothing. Truly. No one has the handbook. It’s a bunch of people who know nothing trying to love and raise others who will ultimately know nothing. I forget all the time that things I think are true are just stories. My perceptions are stories. They’re not a fixed truth.

Your writing is so funny and wry. What makes you laugh?

When it comes to comedy, there’s a grumpy misanthropic type of humor that really gets me. It’s like a loving misanthropy—a love of the soul of humanity, but not necessarily wanting be, like, near it. I get my sense of humor straight from my dad. There was a sardonic us-against-the-world kind of vibe. That’s always been a North Star for me. When you have a fear of intimacy and vulnerability—but, at the same time, a very compulsive desire to spill your guts—humor is a great mediator between those things, because you can give what’s going on, but you can do it with an “I’m okay” bravado that feels protected. I don’t have the self-esteem to be vulnerable and lay it out on the table without wrapping it in a comedic candy coating, because this way I won’t be rejected. I wish I had the self-esteem for pathos.

Plus, in terms of exploring humor, Rachel herself does comedy as a side gig.

This is a pretty Jew-y book, and comedy is a fairly Jew-y tradition: Borscht Belt, Catskills, a funny rabbi. Rachel comes from this theater background, and then ultimately comes to hate theater people for enunciating everything. And she also perceives the Hollywood world, where she works in an office, as a very fake world. Comedy seems like an antidote to those crowds.

I’m really fascinated by the self-love industrial complex. Rachel is really reliant on the laughter of others and the dopamine that comes from it, because there is that deficit within of, dare I say, self-love. There’s this hole inside which could be seen as a physical hole—appetite, hunger—but there’s also that spiritual hole. So there’s that question: What do we put in it? Family approval, desire for love, the illusion of control, money, success, validation. How do we sit with that hole? For Rachel, she’s putting the drug of laughter in that hole. For myself—there’s a lot of shiny shit on the planet. I forget every day that making some achievement, or beauty, or whatever I’ve formed my little censor on as ‘the answer’—every day is a forgetting that there’s nothing outside me that is going to fill it, and then a remembering.

You mention hunger and appetites, which are central to this book. Food deprivation maps out Rachel’s whole life—then turns, becoming a source of indulgence catalyzed by Miriam. In The Pisces, there was, similarly, a “donut incident” that signaled an existential breakdown for the protagonist. Why use food to flag these character shifts?

My longest relationship for sure is my fucked-up relationship with food and my body. I’m really fascinated in the ways, as women especially, we’re forced to control and compartmentalize instincts that are actually interdependent: spirituality, sexuality, and hunger, which are interconnected. Food can really serve as not only a metaphor for a character, but a reflection of how a character exists in the world and sees themselves.

Judaism itself is inextricable with food. If I walk into Cantor’s Deli, I’m home. I read Goodbye, Columbus when I was 10 or 11, and I remember there’s a moment Neil Klugman, the protagonist, talks about “the mayonnaise-y Jews” of yesteryear, like his Aunt Gladys, and “the heaped-with-fruit Jews,” like Brenda Patimkin. I reread the book as I was writing this; I knew exactly what he was talking about, about being Jewish in America.

We only see Miriam by way of Rachel’s gaze. Miriam’s body outwardly encapsulates Rachel’s worst fears about gaining weight, yet she is also incredibly compelling to her. Can you elaborate on this discordance?

I think often what we fear is what we desire. Rachel is definitely afraid of her own appetites—because it’s so pleasurable! Miriam is both the embodiment of that fear and that desire. This is Rachel’s book; we don’t have an independent view of Miriam. How real is anyone we’re romantically obsessed with? How much is the intoxication of love, especially in the early days? People talk about unreliable narrators—we’re all unreliable narrators because we’re experiencing the world and people through our own perceptions.

The book was actually optioned, and I wrote the pilot. In thinking about it as a series, Miriam is going to be embodied and won’t just be seen through Rachel. She will have more agency. It’s always interesting to adapt my stuff for film, because it’s kinda like writing fanfic of your own work.

How does your poetry background filter in when you’re working on a novel?

The way I transitioned from writing poetry to prose is, when I lived in New York, I’d write poetry on the subway, or just like walking. I tend to not like to write at a desk, or anywhere there’s too much perfectionism or rigidity. I want to write when I’m not “supposed” to be writing. Like bed. When I moved to Los Angeles, I couldn’t write poetry and drive, so I started dictating; that’s how the book So Sad Today came to be. The language became more conversational. The delivery changed. When I got the idea for The Pisces, I dictated two to three paragraphs a day. Same with Milk Fed.

Generating all that clay to then sculpt—why would I say in 300 pages something I could say in, like, two? So much has to happen. Like, I can’t believe another thing has to happen. A poem’s happening can be internal, it can be a turn. So with prose, I’m like ‘another action?! Another event?!’ Poetry has given me a love of rhythm and sound. I think in my editing process, I really bring that in.

It’s interesting to think of the narrative process as floating out vocally, rather than set on a page.

The origin of storytelling was verbal, right? For me, it was at first just about not getting in a car accident on the 405 by texting. When I’m writing a first draft, I just want to be a channel. I don’t want to be thinking. So the more I can encourage that flow, the better. When I dictate, I don’t stop to correct anything. Sometimes I can see that Siri is translating things wrong, but I purposefully don’t correct anything until the first draft is done. My first round of edits is actually just trying to figure out what I was saying, and the next round is when I think about audience and audience perception. There is definitely a freedom: in the first draft, I’m trying to encourage as little self-censorship and perfectionism as possible, and I’ve found that writing by hand does that well for me too. Like writing with a juicy pen on a piece of shit paper. Not a nice journal—shitty paper. Being verbal also gets me that lack of preciousness. It’s like prayer! You’re kind of talking to yourself.

What motivated you to write a queer love story?

I’ve been trying to tell this story since I was 19 or 20. When I was in college, I wrote a horrific short story version of this. I’m bi; I’m attracted to all kinds of people. When I write about sex and desire, I have to be attracted to the love object in order to make it good. So I wrote a character that I was deeply attracted to.

Spoiler, if you haven’t read Milk Fed yet: It’s heartbreaking that ultimately this love story can’t go anywhere because queerness doesn’t work with Miriam’s religious orthodoxy or her community’s sense of normativity. It made me so frustrated that that was behind the dissolution of Miriam and Rachel.

I think it circles back to what we were talking about initially: we have the stories we’ve been told, and how important are they to us? Sometimes those stories conflict with a piece of who we are, but we’re scared to get rid of them. As much as I denounce certitude, I’m still afraid to not identify myself with certain stories, which may not even serve me. It sucks that we don’t get to have everything—that what we believe and what we love can be in conflict. That we can’t have romantic euphoria and spiritual euphoria. Humans are limited. Because I was annoyed about that, I had to write about it. We write our obsessions. It’s a debate I was having with myself, first and foremost: How you can have an intellectual belief, but then the heart can say something else?

This content is created and maintained by a third party, and imported onto this page to help users provide their email addresses. You may be able to find more information about this and similar content at piano.io